What is eliciting and interpreting in science?

To elicit individual students’ thinking about science, teachers pose questions or tasks that provoke or allow students to share their thinking about science content in order to evaluate student understanding, guide instructional decisions, and surface ideas that will benefit other students. To do this effectively, a teacher draws out a student’s thinking through carefully-chosen questions and tasks, then considers and checks alternative interpretations of the student’s ideas and methods. In science teaching, it is also important to consider students will have ideas about both the science content and the science practices.

Why work on eliciting and interpreting in science?

Teachers elicit students’ thinking to gain insight into their students’ scientific beliefs and to prepare them to engage in scientific practices. Students have many alternative ideas about scientific phenomena; by eliciting students’ ideas, teachers learn how to design instruction to respond to and build on those ideas. When teachers prompt students to share their thinking about science content or other students’ ideas, students develop the skills they need to make scientific arguments. When teachers practice eliciting students’ thinking, they also build their skills at the related teaching practices of leading and facilitating scientific discussion and supporting students to construct scientific explanations and build arguments.

How do teachers elicit and interpret students' thinking?

Eliciting and interpreting students’ thinking in science often takes place when students are just beginning to learn about a science topic and towards the end of learning about the topic when they are making sense of phenomena they have experienced and investigated. In a lesson about the function of the parts of plants, for instance, a teacher may ask students what function they think the leaves of a plant serve. The teacher may find that many students have the typical alternative idea that the leaves collect water for the plants to use. Because the teacher knew in advance that students often have this belief, they were better able to interpret student responses. They might then use this knowledge of their students’ ideas to design an investigation that would help students understand that leaves do not collect water. After conducting the investigation, the teacher would again elicit and interpret their students’ thinking as the students make sense of their observations and data. In eliciting their ideas, the teacher may find that students have a difficult time articulating their thoughts clearly. To support classroom discussion, the teacher would need to be able to interpret what students are saying.

What are the elements of the practice?

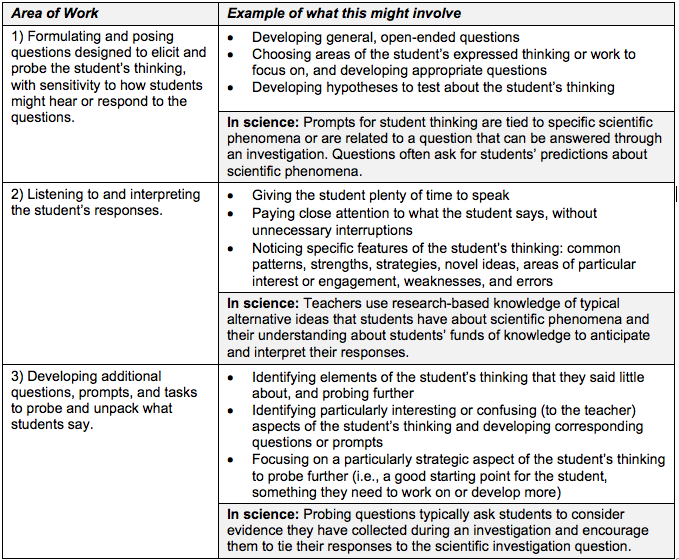

The practice can be broken down, or decomposed, into discrete, teachable parts, described in the table below.

How do we support novice teachers to learn this practice?

In working on this practice in teacher education, we focus on helping novice teachers recognize the importance of anticipating students’ ideas in planning. Some novice teachers may not feel comfortable with science content, and may have similar alternative explanations for the natural world as children do. Supporting novice teachers in anticipating these ideas ahead of time encourages a deeper understanding of the content they are teaching and can boost confidence in enactment by helping them to envision student responses.

Novice teachers also typically have difficulty knowing what kind of language to use when trying to elicit students’ ideas. We support them in this area by providing them with “talk moves” that can be adapted or used in a variety of contexts. In addition, novices may initially ask closed-ended, topic-based questions such as “What is soil?” or “What is a seed?” that elicit students’ fact-based knowledge about a topic, but not their ideas. Talk moves help novice teachers word open-ended questions that elicit students’ ideas about science content, not just their factual knowledge.

We also work with our novice teachers on designing tasks that give students authentic opportunities to share their ideas and not just repeat facts. We do this by teaching novices to use the Engage, Experience, Explain + Argue (EEE+A) framework to develop investigations that require students to engage with phenomena and come up with their own explanations based on the data they collect. In the Engage element, in particular, we support novices in framing an investigation question or problem that provides a context for sharing initial ideas or predictions.