What is leading a group discussion in social studies?

What is leading a group discussion in social studies?

In a group discussion, the teacher and all of the students work on specific content together, using one another’s ideas as resources. The purposes of a discussion are to build collective knowledge and capability in relation to specific instructional goals and to allow students to practice listening, speaking, and interpreting. The teacher and a wide range of students contribute orally, listen actively, and respond to and learn from others’ contributions. From Core Practice Consortium, 2014 and TeachingWorks, 2017.

How can leading a group discussion advance justice?

Facilitating group discussions is an intellectual and a democratic act. The discussions we envision feature participation from a broad array of students who are diverse in demographics, academic achievement, and point of view. Discussions are a place where students work together to consider different perspectives and construct understanding, regardless of students’ social or academic status. At the same time, discussions can easily calcify societal inequities if particular students or perspectives are subconsciously or intentionally marginalized. To combat this risk, teachers keep particular ethical obligations in mind, ensure that all students have opportunities to voice their thinking, demonstrate respect for students’ thinking, and press for consideration of alternative ideas. In other words, discussions can be a lever for redistributing power in the classroom.

Why work on leading a group discussion?

Learning is fundamentally a social activity. People learn from talking through their existing ideas and listening to the ideas of others, especially when the ideas represent differing viewpoints. Furthermore, argumentation is central to the work of historians, geographers, political analysts, and economists, all people who might be considered experts in one of the major social studies disciplines. Through co-constructing ideas during a discussion, students can engage with valuable content and begin to see that social studies is a subject of ever-evolving interpretations rather than fixed truths. Students deserve the chance to create and defend their own arguments, and to consider and critique the interpretations of others. For novices, learning to lead a group discussion is a foundational practice for approaching social studies as inquiry, and builds on other instructional practices such as eliciting student thinking and setting up and managing small group work.

What is the role of leading a group discussion in the social studies classroom?

Social studies inquiry lessons ideally give students opportunities to Engage in the inquiry, Experience analyzing social studies artifacts and Argue for or against interpretations through discussion or writing (a.k.a., the “EEA” framework). Discussion often takes place in small groups during the Experience portion of the lesson, and in whole-class groups during the Argue portion of the lesson. Discussion is particularly fruitful once students have had a chance to explore historical or social scientific sources, and discussions often revolve around the central question of the lesson, such as Was Columbus a hero or a villain? or Should Civil War monuments remain or be removed? After discussions, students are prepared to write arguments taking into account all they have learned from the sources and their peers.

Discussions in social studies often take on a specific structure. Examples of these structures include a Socratic Seminar, Structured Academic Controversy, or debate. In this resource, we use a Public Issues Exploration structure, where students grapple with a current civics or Constitutional history topic and sources of local or national relevance before discussing this issue as a group. Because of this choice, we engage novice teachers in a Public Issues Exploration as students (see Activity 1) and ask them to analyze Public Issues Explorations before leading one in a classroom. Other forms of discussion can easily be used instead of the Public Issues Exploration throughout these activities.

How do we represent this practice in social studies?

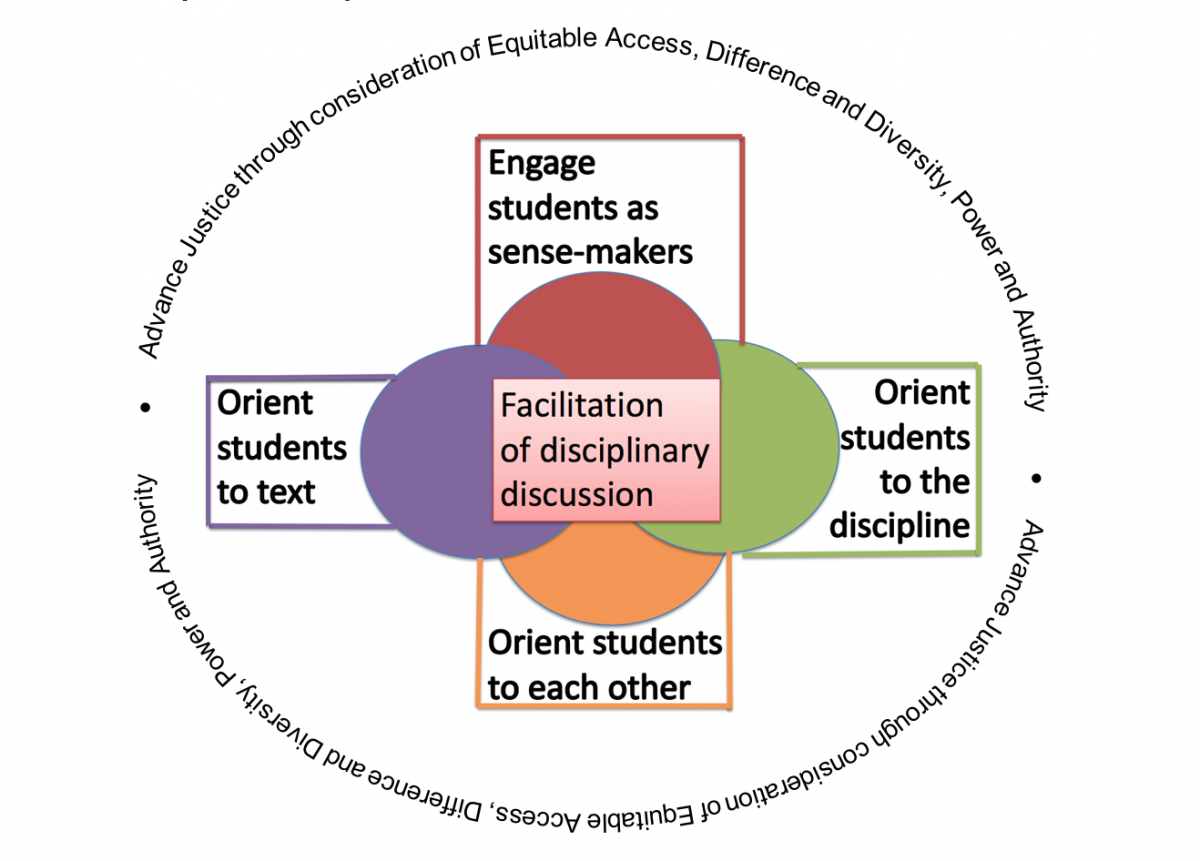

Through work with the Core Practice Consortium, Reisman, Kavanagh, Monte-Sano, Fogo, McGrew, Cipparone and Simmons (2017) represented four areas of work (center Venn diagram) that are necessary to facilitating a rich discussion in social studies. Researchers identified these areas by analyzing the discussions that teacher candidates at two universities led in their field placement classrooms.

Even if you attend to each of these areas of work, your discussion might lead to more learning for some students than others or reinforce traditional power structures in the classroom. Therefore, we also include three ethical considerations (outer circle) to guide teachers’ work and advance justice while facilitating discussions. We explain each below and share some video clips as illustrations.

Engage students as sense-makers: Ask students open-ended questions that have multiple possible answers, that prompt students to think about the content, and that demonstrate curiosity about students’ ideas. This might include asking the central historical question or exploring a historical document. In the clip below, the teacher has students make sense of a visual artifact from the Silk Road region in pairs before sharing their ideas to the class.

Orient students to the text: Orienting students to the text might include asking students to use textual evidence to support a claim, working with students to summarize or make sense of one text, or directing students to a particular part of the text. In this clip, the teacher guides students to identify texts and examples to support their claims about whether post-apartheid South Africa is living up to its promises.

Orient students to each other: This involves asking students to engage with each other’s ideas. This might include referencing a student’s idea, asking a student to rephrase or respond to an idea offered by one of their peers, or highlighting a student’s idea for the class to consider. In this clip, the teacher has students agree and disagree with each other’s ideas about the reliability of sources for learning about the ancient Silk Road. The teacher also connects multiple students’ ideas to facilitate other students commenting on the contributions of their peers.

Orient students to the discipline: Orienting students to the discipline involves highlighting when students are doing or prompting students to do authentic disciplinary work. This might include asking questions that rely on disciplinary ways of reading and writing, highlighting the claim-evidence structure of historical arguments, or making a comment about what it means to study history or social sciences. In the first video above at 1:30, the teacher highlights the work of one student who changed her interpretation after hearing new information as a key way that historians think. In the same video at 2:11, the teacher highlights students’ disciplinary work in comparing multiple sources.

Equitable Access: All students should have access discussions in social studies. Examples of attending to equitable access might include the following:

- Giving all students a chance to participate through quick “turn and talks”

- Modifying questions to provide entry points for all students

- Highlighting contributions from students with less power and authority

- Providing visuals to help students track on the discussion

Difference and Diversity: Discussions in social studies should value and bring out diverse perspectives. Examples of attending to difference and diversity might include the following:

- Choosing content representative of diverse social groups and identities, or voices that are underrepresented in social studies curriculum

- Encouraging students to challenge one another’s ideas

- Questioning perspectives in historical text

- Recognizing that students’ participation patterns may vary based on their cultural backgrounds

Power and Authority: Discussions in social studies can invert traditional power structures of whose voices are heard and valued. Examples of attending to power and authority might include the following:

- Noticing how often the teacher speaks and how often students speak

- Changing the teacher’s location in the room (i.e., away from the front)

- Questioning the reliability of authors and sources in text

- Orienting discussion around student ideas

- Considering when to revoice a student’s idea or when to let their idea stand on its own

- Assessing the way diverse social identities are portrayed in the text and in the classroom

How do we decompose the practice into learnable parts?

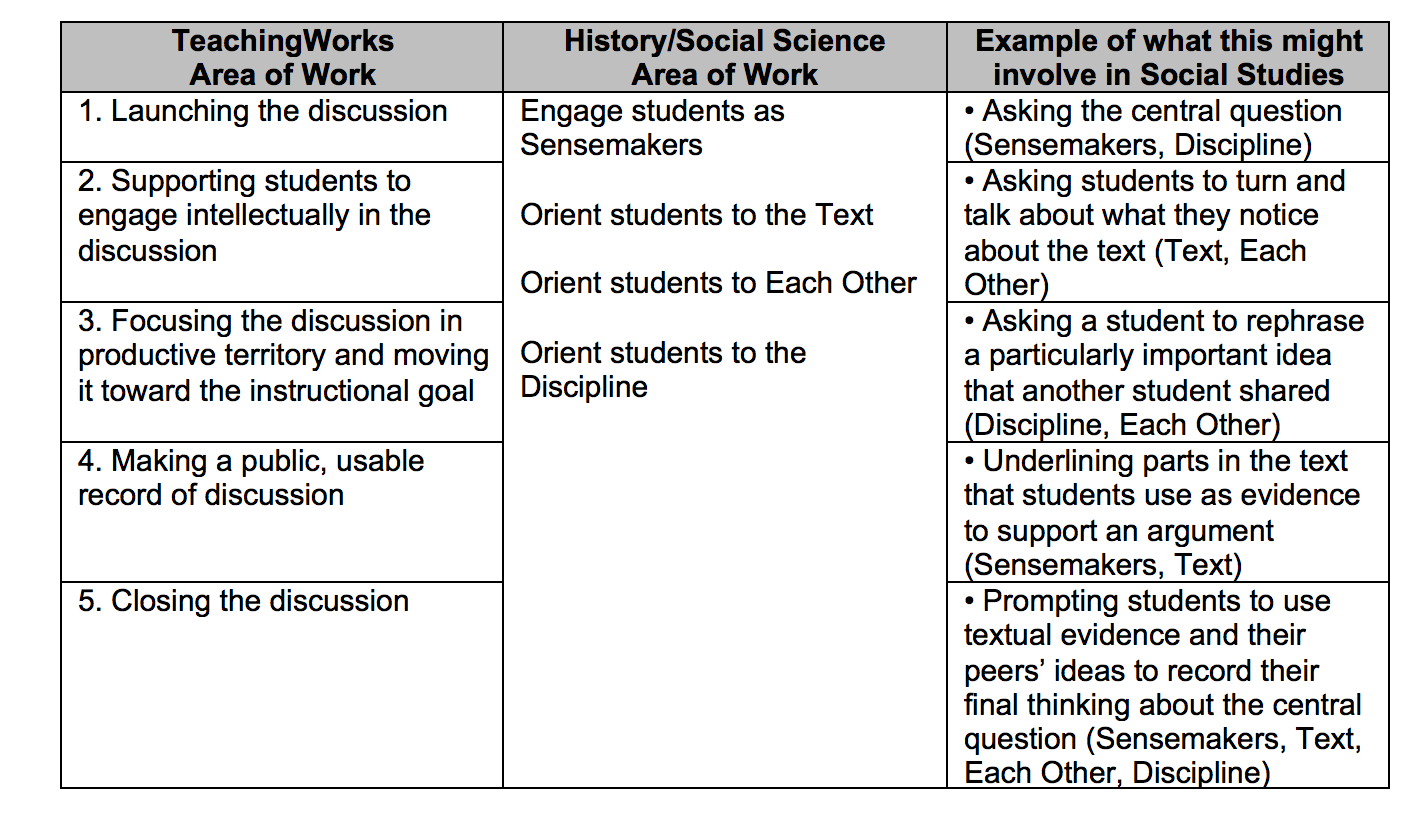

In the chart below, we map our Social Studies/History conception of discussion (middle column) onto the TeachingWorks areas of work in discussion (left column). All of the history/social science areas of work occur across the various TeachingWorks areas of work. Each social studies example in the right-hand column corresponds to an aspect of the TeachingWorks areas of work. In the right-hand column, parentheses label which History/Social Science area of work the example represents.

Supporting Novice Teachers

In the social studies methods course at the University of Michigan, we provide examples of teachers leading discussions in order to represent discussion facilitation as a practice focused on generating student talk and co-construction of ideas rather than teacher-centered talk. When novices try leading discussions on their own, we often find that novices engage students as sensemakers and orient students to the text, but struggle to orient students to each other or to the discipline. We have found it important to help novices lead discussions in ways that move students towards a learning goal rather than simply encouraging open sharing, and we use central inquiry questions that teachers ask multiple times throughout the lesson as a way to focus lessons on those learning goals.